Perceptions of insects – Philias and Phobias

Article by Dr Franziska Kohlt, University of York

Insects seem to be uniquely polarising. But why is it we react so strongly to insects? And why is it that we seem to put up with some of them, on second thought, but not others?

This Insect Week, a panel of entomologists, cultural studies experts, and science communicators, in conversation with the public, decided to get to the bottom of it.

We probably all have a memory of the first, or that one particularly memorable insect encounter that’s defined the way we think about them. And while, for some of us, that memory might have been last week’s BBQ where once again wasps were after our burger before we got to enjoy it.

But some of those defining memories might actually be a lot further back and found in places where we do not expect them. Did, for instance, the portrayal of the ladybird in Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach as motherly and caring make you think more positively about them, well into adult live? Children’s literature and popular culture can be a major influence shaping our perceptions of insects – and their portrayals in it can differ quite significantly depending on when and where we grew up.

In the Czech 1957 cartoon “Krteček” (“Little Mole”) Zdeněk Miler’s for, instance, portrays insects as overwhelmingly positive: they are a hard-working collective, efficiently delivering of the several stages of fabric production in “How Mole Got His Trousers”.

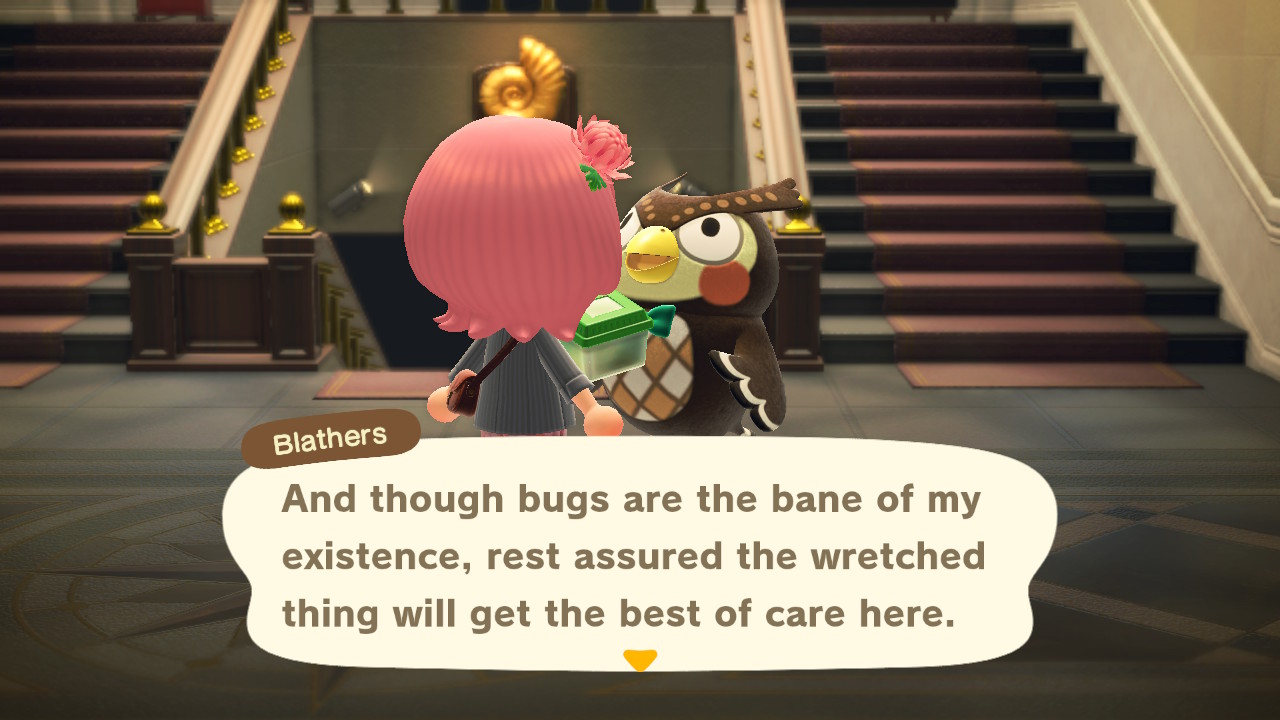

More recently, Animal Crossing: New Horizons, which some of us may remember from the early days of the pandemic, offers a comedic counterpoint. The owl Blathers, curator of the game’s museum – in charge, amongst others, of its entomological collections – can imagine nothing worse than insects. His tagline, whenever the player delivers a required insect specimen, being, that “bugs are the bane of my existence”, usually accompanied by exclamations of horror.

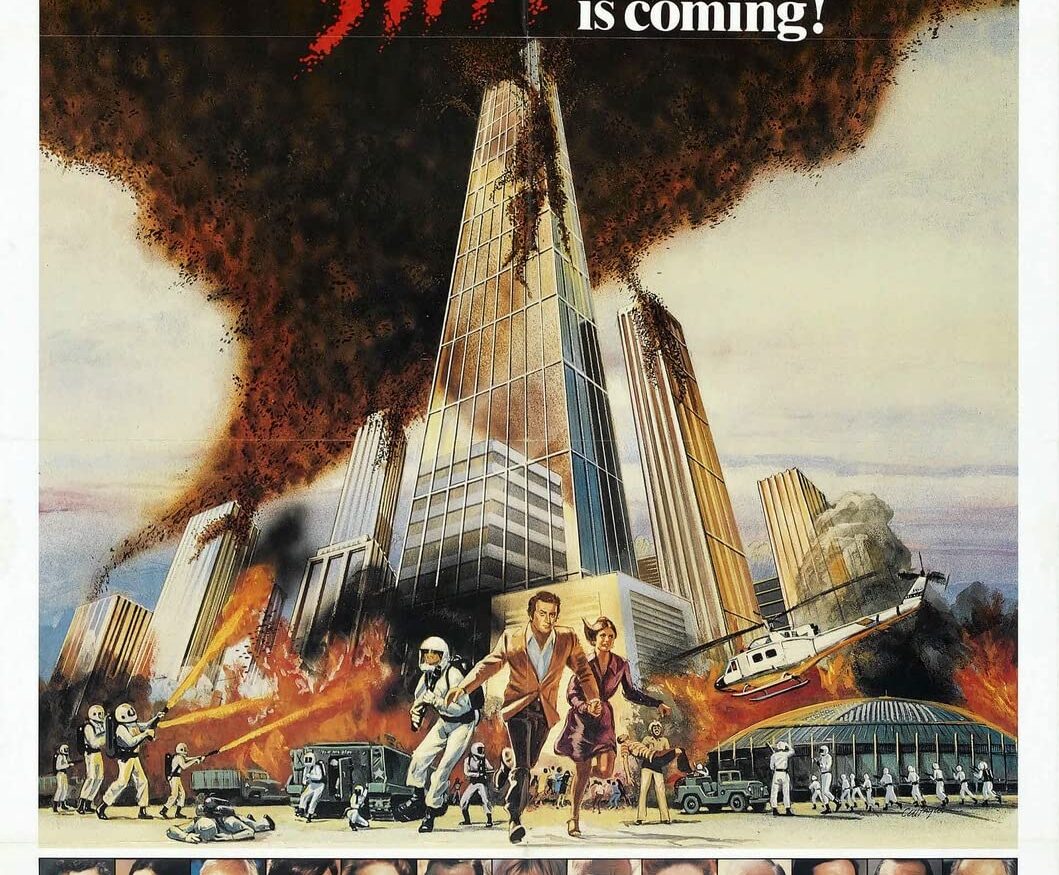

This fits much more into the first thing that might have come into many of our minds – the killer insects of movies like Them!, with giant irradiated ants or Tarantula!, with a giant irradiated tarantula.

But even though, Liam Hathaway explains, their insects are in one or more aspects over-exaggerated these films do often evoke real-world ecological and environmental issues, and anxieties attached to them. Kingdom of the Spiders reflects insidious pesticide issues; The Swarm links to the killer bee hysteria of the 1970s; and Mimic connects to anxieties surrounding genetic engineering.

They also collectively remind us just of insects’ crucial ecological functions and show us that if we attempt to eradicate entirely, biologically manipulate or infringe upon bugs too much, it will likely knock our fragile ecosystems off balance. This is why these films are ultimately far less concerned with depicting bugs purely as monsters, but show them fighting back against unscrupulous or avaricious humans ignorant about the environment.

Key influences on our perceptions of insects can not only be found in popular culture. Perhaps unsurprisingly, our views of insects, are shaped especially early on in life, by parents, but also by teachers. As Verity Jones found in her research, working with schools, the way a teacher reacts can shape a student’s perception of insect behaviours, ecology and whether or not they are perceived as a threat, to themselves or more globally, for the rest of their lives.

And yet it’s not all black-and-white: Prof Jones’s workshops show us there’s plenty of room for positive conversations about insects in classrooms. And, as a member of our audience was keen to point out, in popular culture too: it was, after all, Mothra who saves the day in Godzilla. And even Blathers, at times, has to concede that insects are beautiful and useful.

So there is another story to be told – hold different narratives for us to re-discover insects, one that puts the insects, and their often crucial place in ecosystems, centre stage. And our own preconceptions can be a good point to start.

While bees have undergone a recent surge in popularity, Seirian Sumner has been on a mission to rehabilitate the reputation of wasps, by revealing to us the unseen stories about wasps that make us understand their behaviours a lot better, or even make them relatable.

And these stories are also practical. Do you start flapping and breathing hectically as soon as that wasp comes for your BBQ? Why you should avoid this has a very good reason: wasp’s main predators would behave in precisely this way to signal their predatorial intentions, and wasps have evolved to react to even minute changes in CO2 levels that are caused by hectic breathing to identify a potential predator. Chances are, they are probably just checking out your burger as a potential food-source, as much as you would.

Prof Sumner’s research shows that there can be quite a gap between what insects and the perceived and actual behaviours and their purpose. She found that the public, for instance, rate highly bees’ ability to pollinate, and their “usefulness” – whereas wasps are mainly defined by their sting. Much to Prof Sumner’s frustration, because, really, only some species of wasps actually sting – and there are, equally, some species of bees that do so. But there were also positive surprises. Wasps scored top marks in their “usefulness”, when it came to their wider role in the ecosystem, as predator of pests. And Prof Jones also found that their “ecosystem benefit” certainly seems to be a main story that swings perceptions of insects from negative to positive.

But are there other good strategies for changing perceptions of insects?

Prof Jones and Dr Kohlt agreed that shifting the narrative away from the anthropocentric perspective can be helpful, as giving over the stage to the insect, and why it behaves the way it does, can aid us to understand the complexity and the often-fragile balance of our ecosystems. Initiatives Further, citizen science initiatives, such as the “Great Wasp Count” gives everyone the opportunity to witness and contemplate insect behaviours in the wild, and outreach introducing school children for instance to entomophagy – insects as food source – tackles the “yuck” factor head-on, and introduces through it to ecological challenges, in which insects continue to play a key role.

Other ideas include poetic figurations of insects, which often portray them in an amazingly positive light. Christian and Islamic in religious poetry often uses the moth as metaphor for the human soul, comparing their metamorphosis – from soil-dwelling larvae to caterpillars nourished by life on Earth, to beautiful winged creatures, drawn from night to light – to the transcendence of the soul, human emotional and spiritual growth. The Greek word for the soul – “psyche” – even came to name an entire class of moths – “psychidae”, and the image lives on. The Oscar-winning title-song of recent Disney-movie Encanto, “Dos Oruguitas” (“Two Caterpillars”) maps out the spiritual growth of Mirabel and Alma “Abuela” Madrigal from sorrow to flourishing – a moment celebrated with a radiant swarm of golden butterflies ascending into the air.

Has there been a story that has changed the way you’ve thought about a particular insect, or insects in general?

Tell us in the comments of the recording of our Panel Discussion which can be found on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3A1OJtEpfAY&t=11s