How nineteenth century Britain became obsessed with insects

The Victorians were fascinated with insects. This is as obvious as it can be elusive, as insects themselves often are. The Victorians embraced insects for their beauty, their mystery, and their changeability – all aspects of utmost concern to this era of unprecedented change, cultural, technical, political as well as scientific. In constant search for their own identity, insects became uncanny ambassadors of Victorian culture, representative as well as unsettling, masquerading and revealing at once.

Fashionable insects: explorations and innovations, taxonomies and nonsense

There is no question that insects were en vogue. Beetles and butterflies were omnipresent in Victorian art, which is perhaps not too surprising: they had always been favourites in ornamentation and fashion. The dress made of beetle wings which the celebrated Victorian actress Ellen Terry wore as Lady Macbeth, illustrates perfectly how the Victorians combined the increasingly popular study of natural history, which often included laymen collecting insects, with fashion.

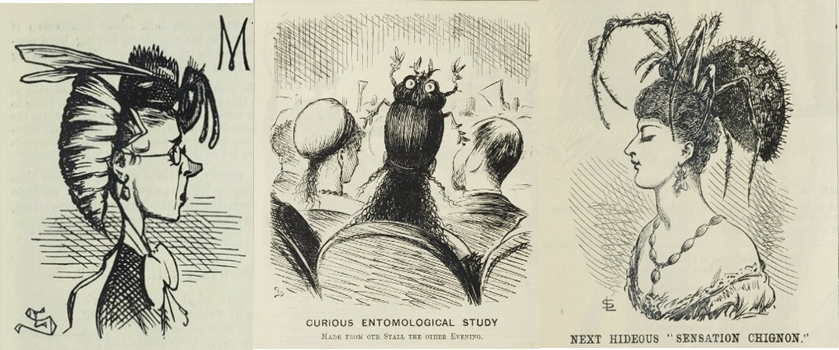

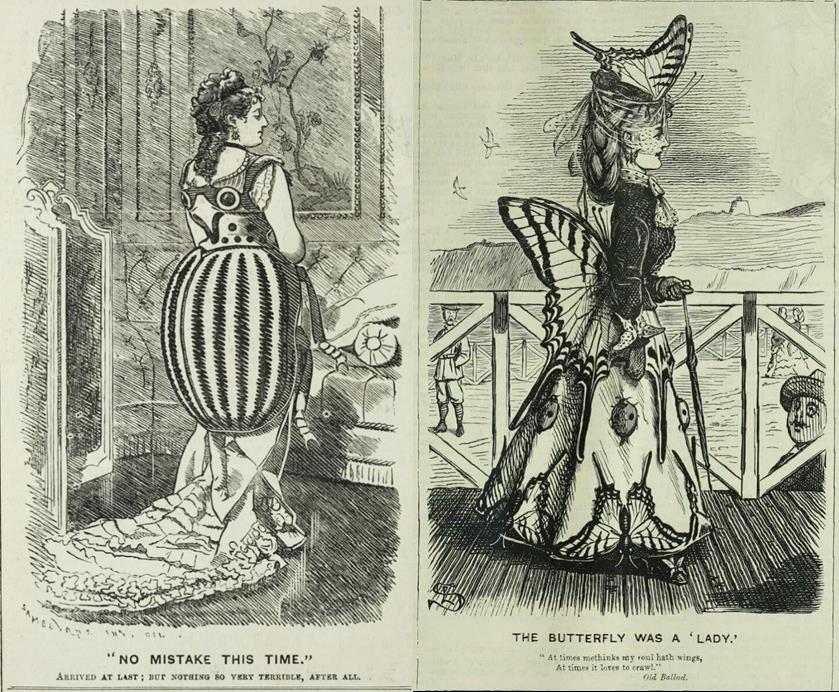

A slightly different take on the aesthetic side of the study of nature, as well as the beneficial effect it was believed to have on individual character and society, was offered by Punch illustrator Linley Sambourne. Mocking the haphazard and indiscriminate application of science to all areas of society for the sake of its improvement, a series of caricatures entitled ‘Designs after Nature’ presents the results in ladies’ fashion. Victorian female dress, known for its ornate and lavish embellishments apparently benefitted from the advantages of biomimicry – drawing its inspiration from the insect world. The results were peculiar, but enticing: a snail’s shell and beetle’s exoskeleton supported or even replaced the bustle skirt – and what was first meant as parody could, in fact, later in the century be found in costume catalogues.

But ‘aesthetically pleasing’ is not the only thing popularly associated with insects. Particularly the unsettling potential of the creeping and crawling creatures absorbed the creeping changes unsettling the Victorian age in literature and illustration, from imperialism to advances in technology. That Sambourne’s dresses blurred line between human and animal natures was all but coincidence in an age in which theories of evolution gained wider public profile.

This manifests in playful manner in Edward Lear’s work, whose first career was notably as a naturalist, most famous now for his illustrations of birds.

Playing with scale, Lear’s nonsense creatures were magnified to threatening, monstrous dimensions, similar to the way in which otherwise invisible bacteria gained importance under the microscope of the scientist. Imitated in art and literature such distorted visions reflected on aspects of the destabilised hierarchies within creation. Lear’s sketches of men, including himself, with animal-features as bird or beetle, man and animal are notably often of the same height, evolutionary boundaries melting away.

The creation of new hierarchies and taxonomies by science, and the sheer endlessness of the effort of cataloguing new species however itself became subject to mockery. Most evident in Lear’s nonsense botany, a favourite of satirists was nomenclature, which in the work of Lear’s contemporary Lewis

Carroll leads to extraordinary entomological neologisms.

In the sequel to his immensely popular Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) Alice turns explorer of the insect population of the forest in Through the Looking-Glass (1871). Instructed by a chicken-sized gnat, Alice begins cataloguing such novels species as the ‘snap-dragonfly’ and the ‘rocking-horsefly’, as well as their habits. The fleetingness of insect – and human – life does not pass her by, as the following scene reveals.

In the sequel to his immensely popular Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) Alice turns explorer of the insect population of the forest in Through the Looking-Glass (1871). Instructed by a chicken-sized gnat, Alice begins cataloguing such novels species as the ‘snap-dragonfly’ and the ‘rocking-horsefly’, as well as their habits. The fleetingness of insect – and human – life does not pass her by, as the following scene reveals.

‘Crawling at your feet,’ said the Gnat (Alice drew her feet back in some alarm), ‘you may observe a Bread-and-Butterfly. Its wings are thin slices of Bread-and-butter, its body is a crust, and its head is a lump of sugar.’

‘And what does it live on?

‘Weak tea with cream in it.’A new difficulty came into Alice’s head. ‘Supposing it couldn’t find any?’ she suggested.

‘Then it would die, of course.’

‘But that must happen very often,’ Alice remarked thoughtfully.

‘It always happens,’ said the Gnat.

Transforming Selves

Wherever insects featured, death was not far. Self-improvement, a notion intimately connected to the transience of life, was a core part of the Victorian mindset, and was thus present in the children’s literature and natural history books to which it gave rise. Insects, and their amazing capacity for transformation, played a core part in these narratives.

The life-cycle of insects became a model entomological bildungsroman. For instance in Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies, a children’s parable of evolution, the transition from a lower into a higher form symbolised the progression from immorality to morality. The protagonist Tom observes a dragon-fly hatching from what was before ‘a rather ugly fellow’, and caddises turning into winged flies, and ‘began to long to change his skin, and have wings like them some day.’ As he however fails to improve, morally, evolution turns against him, and he turns form a semi-human water-baby into an eft, and a prickly sea-egg. Natural History reformed the morality tale and naughty Victorian children were regularly turned into insects that could compete equally with Kafka’s Metamorphosis and Hooke’s Micrographia.

These metamorphoses of insects were also used for darker analogies. The more sinister truth of Kingsley’s story is of course that Tom, a little chimney-sweeper has drowned and his underwater journey is his dying vision. Tom only awakes after the fairies had freed him from his ‘husk and shell’ – which is left behind on earth to be buried. Kingsley had used this image writing to his publisher Macmillan, after the death of his young son. The human body was but a ‘chrysalis’, and earthly death was the moment the soul broke forth into real life in ‘full-winged flight’.

Creepy Crawlies

Especially around the fin de siècle, the part of the Victorian age haunted by doppelgangers and supernatural threats, which gave us Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) or Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), insects populated the darkest corners of Victorian fiction.

For instance, in Richard Marsh’s thriller The Beetle (1897), the mysterious Beetle exerts mesmeric mind-control and takes control of the human body. With its capability to transcend human limits it is present in spaces where one cannot see it, it penetrates into darkened locked rooms, under duvet covers, and thus interrogates anxieties surrounding gender, race and technological progress that preoccupied Victorian minds.

The moral confusion over the mimicry and shape-shifting properties of insects that had exacerbated Darwin’s and Wallace’s studies explain a rise in the presence of leeches and parasites in late-Victorian literature, such as Stoker’s The Lair of the White Worm. But it was Stoker’s earlier novel Dracula (1897) which has fastened its grip on the imagination of its readers.

Super- and sub-human at once, Count Dracula’s features were on the one hand distinctly animalic, but on the other hand, also informed by the fear of the invasive blood-sucking and invasive potential of insects and parasites, the fear of spread of infectious diseases through them, and the possibility of degeneration and extinction, which have since never seized to spiral into new forms of popular culture renderings of vampires and zombies – or their, at times overzealous, interpretations by psychoanalytic critics.

With progress in medicine and technology the Victorian fascination with insects transformed into an obsession with germs, contagion and disease in the age of literary modernity, a development, that has its roots firmly in the insect as an embodiment for unsettling thought.

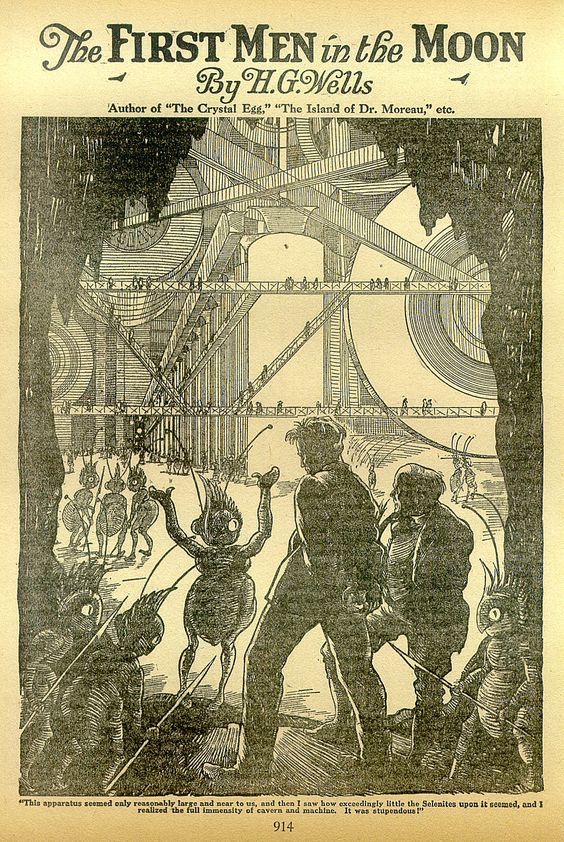

Insects were everywhere, wherever the Victorians came from, or travelled to, as the ‘father of Science Fiction’ H.G. Wells illustrates at the dawn of modernity. His prophetic account of modern warfare in ‘The Land Ironclads’ (1903) likens tanks to large metallic insects, the Selenites in The First Men in the Moon (1901) were distinctly insect-like, and his first rendering of the Martians in the short story ‘The Crystal-Egg’ (1897) imagines them as bat-like creatures – like Stoker’s parasitic Dracula, they eventually consume the human life of their observer. As the long-legged creatures in his more popular War of the Worlds (1898) they embody the fears posed by modern imperialism, advanced technological progress, and an unsettled hierarchy in nature, in which the small but fierce and almost invisible population of the insects holds power comparable to the apocalyptic scenes of the Bible’s Book of Exodus.

It remains to be seen where the journey of literary insects will take us to in this century. But perhaps, roles have already reversed.

About the author

Franziska Kohlt is a Doctoral student at the University of Oxford, where she is working on a thesis on dreams and visions in the works of Victorian fantasists and the emergence of the sciences of the mind. She is interested in the intersections of literature, science and visual culture, and has recently published an article on Lewis Carroll and Victorian Psychiatry uncovering the origin of the ‘Mad Hatter’ and his Tea Party and explaining what Alice has got to do with Asylums. You can follow Fran on twitter @frankendodo and visit her website .